Memoir Blog # 24 Ninoy Aquino – The Boy Wonder of Tarlac

Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr. was born on 27 November 1932, thirty-eight years to the day before the Bolivian artist Benjamin Mendoza tried to assassinate the Pope at Manila International Airport. But it was not Pope Paul VI who was destined to die while disembarking from his plane in the Philippines. On 21 August 1983, Ninoy would perish, a martyr from a single bullet wound to the head, gunned down as he returned from exile in the United States.

The alleged perpetrators who, many believed, included Imelda Marcos, and her husband’s cronies, Eduardo Cojuanco and General Fabian Ver, were never punished for the crime. But there was little doubt in the minds of some U.S. State Department officials and the Philippine judiciary committee, set up later to uncover the truth, that they were the guilty parties.

Since his murder there have been many glowing tributes, a good many myths and a great many lies written about the young Senator from Tarlac, Pampanga. Most Filipinos believed he was the strongest candidate to become the next President when, in 1973, Marcos would be legally forced to step down after serving his second term. And there are still many Filipinos today who truly accept the myth that Ninoy would have made a benign President, a far cry from the dictator that Ferdinand Marcos became. To those who had suffered for so long, Ninoy represented a new era of hope, of integrity, of justice, a healer of the devastating wounds inflicted on the country and its people by almost two decades of Marcos’s rule.

In fairness to Ninoy, by 1983, after his seven years in prison, his self-confessed spiritual awakening and his three-year exile, maybe he had changed radically and things might have been different. But whether his supporters at the time liked to admit it or not, Ninoy and Marcos had much in common. They both came from similar family backgrounds. From an early age they both possessed an inherent aptitude for politics and an unswerving belief in their own destiny. They shared a boundless energy, an immense ego and a single-minded ambition. They were each blessed with a charismatic personality. Both were braggarts, liars and bullies, having little sympathy for anyone who opposed them. They both studied law before entering politics. As politicians they spoke the same language. They talked about when, not if, they became President of the Philippines. In politics, too, they masqueraded as nationalists when, in fact, they were both authoritarians. They instinctively knew how to win support and favours within the U.S. government. In fact they probably knew more about the inner workings of the Pentagon than most officials working there.

It is hardly surprising then that they strongly resisted comparisons but there is little doubt they were too much alike for comfort. Each, undoubtedly, recognized his own personal character flaws in the other. Perhaps that’s why they ended up such implacable enemies. They illustrated perfectly the oft-quoted line from the movie, High Noon, “This town ain’t big enough for the both of us!” In the case of Ferdinand Marcos and Benigno Aquino this phrase was never so true.

Despite Ninoy’s indignant protests when challenged about his views on dictatorship and despite being branded a Communist by Marcos, he was, without doubt, a committed totalitarian. In an interview with Asiaweek Magazine he even admitted that had he been President in the early 1970’s he, too, would have seized emergency powers and declared martial law, just as Marcos had done. And, despite the enduring public perception of him as a supreme nationalist, Ninoy was, perhaps, even more pro-American than his adversary.

This fact scared Marcos the most. He knew Ninoy had powerful friends within the U.S. government. He realized too that, at any time, the Americans could remove their support from him and place it with someone more willing to tow the American line, someone more malleable, someone who had long claimed to be working hand in glove with the CIA – his nemesis, Ninoy Aquino.

Thus Marcos viewed Ninoy as his shrewdest, most dangerous and most threatening rival. And there is no doubt he had real grounds for his fears. He must have known there were many prevailing voices within the American administration, some openly hostile to him, such as Assistant Secretary of Defence Richard Armitage, Assistant Secretary of State Paul Wolfowitz and the NSC’s Asian expert, Richard Childress and many others who more were prepared to ditch him for the more compliant Aquino.

I became aware of this mutual hatred very soon after I arrived in Manila. Ninoy was well established by then as a very vocal opponent to Marcos. As the only Liberal Party Senator who survived Marcos’ landslide victory in 1965 he relished the prospect of speaking out against Marcos’s increasing stranglehold on the country’s political, judicial and commercial institutions. Ninoy was an unashamed loud-mouth, brash, uncompromising and, above all, fearless. He effectively used the media, the floor of the Senate and political platforms all over the country to wage his personal war against Marcos despite increasing risks to himself.

Not a day passed without some news coverage of Ninoy’s latest tirade against corruption, croney capitalism, the development of a police state or tax evasion. As a former reporter and foreign correspondent for the Manila Times, the young Senator had many friends within the media who were equally worried about Marcos’s expanding powers and who were more than willing to devote many column inches to Aquino’s accusations. Like many others I, too, was fascinated by anyone who was brave, or foolhardy, enough to stand up and oppose Marcos and I relished the opportunity to meet him.

So, when a journalist friend, Sylvia Mayuga, called me up with an invitation to join her and a group of reporters to stay overnight at Ninoy’s home in Tarlac I grabbed it.

”What’s your interest in him?” I inquired.

Sylvia was, undoubtedly, one of the most astute young journalists in Manila and I was eager to hear her opinion on the “Boy Wonder of Tarlac”, as the newspapers had dubbed him.

On the other end of the phone Sylvia laughed. “You know, Caroline, he is going to be our next President. That’s my interest in him!”

The emphasis on the “is” intrigued me. It was evident by the sarcastic tone of her voice Sylvia was not a Ninoy fan. Although I also knew from discussions we’d held deep into the night in Los Indios Bravos she was also vehemently anti-Marcos.

“I’ve been reading some of Ninoy’s speeches. He’s got a big mouth that’s for sure. How long can he continue like that and get away with it?” I asked her.

“Good question. But your guess is as good as mine,” Sylvia replied. “He truly believes he’s the saviour of the Philippines so I imagine he’ll carry on his crusade until he’s either President or dead! Most people believe he’ll be President.”

It was amazing to me that so many people assumed the next election due the following year, 1969, was a foregone conclusion. There simply was no one else to challenge Marcos. If you believed what you read in the papers it would be a one-man race. Members of the opposition parties, having been trounced so soundly in 1965, were simply not prepared to raise their necks above the political parapet.

Sylvia told me we were to leave from the domestic airport on the dot of four o’clock on Sunday afternoon. She stressed that Ninoy had made it clear that anyone not present at the appointed time would be left behind.

“The Senator,” she chuckled, “considers tardiness one of the seven deadly sins.”

Naturally, not wishing to miss the opportunity of meeting this larger-than-life personality the press invariably described in such glowing, reverential terms, I was inside the airport terminal with time to spare.

But four o’clock was approaching and there was no sign of the Senator.

“He’s flying in from a meeting in Batangas!” whispered one fawning aide in my ear as though that explained everything.

One minute to four – still no sign. It couldn’t be, surely, I thought, that the conscientious Senator who could not abide tardiness in others was actually going to keep us waiting? No, surely not.

Just then an agitated courtier rushed in from outside.

Just then an agitated courtier rushed in from outside.

“The Senator’s arriving – now!” he announced breathlessly.

That was obviously the cue for us to form a welcoming committee on the tarmac to greet the Boy Wonder of Tarlac. Dutifully, we filed outside. Sure enough, amid a whirlwind of dust and grit kicked up by the rotor blades, there was the Senator’s helicopter alighting right in front of us. I looked at my watch – on the dot of four. I had to admit it. I was impressed.

My first glimpse of the Senator was of him descending from the helicopter. I watched as he rushed, head bowed, towards the plane that was waiting, engines revving, alongside the terminal building. There was no time for introductions. The Senator was in a hurry. Ninoy’s aides hustled us across the tarmac.

Once up in the air there were still no introductions. Well, I reasoned, I guess he must know the other journalists and, as I had attracted enough column inches since my arrival in Manila to rival his own, he must have known who I was. So maybe introductions at this point were superfluous.

I looked at him. At 36, Ninoy could easily pass for his late twenties. He was chubby, no doubt, with a fleshy, boyish face framed by huge black-rimmed glasses and topped by a full head of dark hair with no tinge of gray. He wore a barong-tagalog, clean, well-pressed and probably new. And in his plump fingers he clutched a shiny new walkie-talkie.

Sylvia nudged me and pointed out of the window. Appearing below us was the vast flat landscape of Pampanga, prime agricultural land known as the rice bowl of the Philippines. One of the Senator’s aides proceeded to point out the extensive borders of the Senator’s land – or, as I understood it by a whisper in my ear from Sylvia, the land belonging to the Senator’s wife, Cory Cojuanco. But, of course, the aide failed to mention that small fact and Ninoy failed to correct him.

The boy Senator was busy playing with his walkie-talkie.

“Come in Charlie! Come in Charlie!”

The machine gurgled and spat back at him.

”Yes, Sir, Senator, Sir. Can I help you, Sir?” A deferential voice at the other end crackled.

“Charlie, where is my car right now? Will it be at Luisita Airport in time to pick us up?”

The machine spluttered and hissed again.

“Yes, Sir, Senator, Sir. Just a minute, Sir. Someone in the office spoke to the driver five minutes back, Senator, Sir. I’ll check to see what the message is, Sir!”

There were some sound effects in the background and then, “Hello, Sir! Jaime just spoke to your chauffeur, Sir. Apparently he is traveling on the main highway at 80 kilometres an hour, just before the turn-off. He will be there precisely at 4.27 to collect you! Anything else, Sir?”

“No thank you, Charlie. Over and out!”

The Senator switched the machine off but kept it in his hands, playing with it, turning it over, marveling at it. I wondered at the spectacle of a serious politician playing with a child’s toy. So far he had ignored the group of journalists and I could tell from their expressions they were beginning to feel a little neglected.

Fifteen minutes later we were there. And still not a word from the Senator to his traveling companions. As we got down from the plane someone tried to strike up a conversation of sorts.

“Uh, Senator, Sir, I wonder if uh…..”

But the Senator wasn’t listening. He was striding down the steps playing with his walkie-talkie, informing the staff at home we had arrived and totally oblivious of any commitment he might have had to his guests.

The minute we landed in Tarlac the weekend started to unfold like I imagined a weekend at the Kennedy’s Hyannis Port compound would be. The accent was focused on ego, wealth and sport. No sooner had we been shown our rooms than we were whisked off to be given the grand tour of the vast estate of Hacienda Luisita. The Senator had changed from his formal barong-tagalog into an impeccably tailored riding habit courtesy, I was informed, of a renowned men’s outfitters in Savile Row. Despite his bulk the Senator certainly looked elegant! And I thought what a perfectly fitting outfit for presenting us his string of polo ponies each one, he told us with pride, flown over from Ireland.

Ninoy pointed in the direction of a lush meadow where a magnificent looking steed was munching grass and whisking away the myriad flies with its tail.

“That’s my Arab stallion,” he boasted, “It cost me $160,000. He’s the best stud in the Philippines.”

I wondered aloud how one compared one stud with another. Did you line them up in front of the mares and then measure the results? But the Senator was in mid-flow and not about to be interrupted by such a churlish question.

“For his service alone I earn an annual income of around $26,000. I charge $2000 a time!”

He moved on and, like faithful hounds, we followed. In an adjacent field Ninoy pointed out a one-month old foal.

“I’ve already been offered $30,000 for that one on the day it was dropped. But I’m thinking why should I accept $30,000 for it when I can easily enter it in the sweepstakes and walk away with $120, 000?”

Why indeed, Senator? I thought. My brain was getting confused with all this talk of money. Maths had never been my strong subject.

“Anyone for a ride? Sylvia? And how about you, Caroline?”

Abruptly Ninoy jolted me back to the present. I could see he was itching to show off his prowess in the saddle.

But nobody wanted to ride, least of all me. I had no intention of making a fool of myself. The others felt the same. The Senator looked disappointed. So, instead he bundled us all into two Super de Luxe Land Rovers to complete the tour of his vast property. Again he failed to say the land was part of an 18,000-acre estate belonging to his wife’s family, the Cojuancos.

With a sweeping gesture Ninoy informed us, “I employ eleven thousand workers here. And I provide for each one of them.”

Just then the Senator jammed on the brakes to point out a few historic landmarks of Hacienda Luisita.

“There’s the church I built for my employees. There’s the community centre where they dance, sing, play the piano and play billiards, whatever it is they do. And, over there, that’s the school. By the way, each child receives free education up until high school. That’s their bank. And that building there, that’s their movie house. And over there, that’s their town hall where they can hold political meetings. There’s the surgery and the hospital. They have free medical and dental treatment and…….”

I was beginning to wish I lived in this utopian heaven where everything was provided for free. But I was more anxious to interrupt this self-congratulatory monologue so I asked, “How about birth control, Senator?”

My question failed to faze him. As the consummate politician Ninoy had a ready answer.

“Well, each woman is provided with a free loop.”

Of course, I should have known. But I was in a combative mood. I wasn’t going to allow him to get away with it that easily.

“You mean to say, Senator, that you actually give 5000 women no other choice than to use an IUD when they know their church’s feelings towards birth control? Do some of them hesitate or is your word more final than the Pope’s?”

“Around here it is!” Ninoy beamed back at me triumphantly. He was far too seasoned a politician to fall into the trap I was setting.

“And what do you ask in return from your employees?” I persisted, unwilling to be beaten in this altercation.

“Very little. That they work on the sugar plantation, which I shall show you in a minute. And that they vote for me, naturally!”

Well, from that I deduced, without much difficulty, Tarlac could not hope to have any political future other than Senator Aquino for many years to come. After all, at 22 he had already been elected the youngest Mayor of the local town, Tarlac. At 28 he had been appointed the youngest provincial vice-governor and, at 30, he had won the gubernatorial election by the highest majority ever. At 32, ever in a hurry to fulfill his destiny, Ninoy became the youngest Senator. So, much like his nemesis Marcos, Ninoy’s rise to power had been mercurial.

The Senator’s Land Rover drove us over some of the 250 kilometres of road leading through the private estate.

“I got married when I was just twenty-one,” he told us. “And from the age of twenty two I took over the administration of the Hacienda Luisita and the Tarlac Development Corporation. It was hard work for a young man, I can tell you.”

After he had called ahead on his faithful walkie-talkie to the refinery to warn them of our impending arrival, he proceeded to inform us about the many different strains of sugar grown at Hacienda Luisita. He told us how he had spent many long nights alone slaving over the thousands of cross-breedings in order to extract the perfect specimen. At least I was being educated, I thought. It had certainly never dawned on me before that sugar came in anything more than just the three varieties, refined white, golden demerara and dark molasses.

From 1958 onwards Ninoy’s major concern, he told us, was to keep the sugar plantation alive and solvent. He removed his glasses to rub his forehead as though just thinking about those early days gave him a headache.

“At the time I took it over it was a sinking ship. But I never gave up hope and I managed, single-handedly, to bring it back into full production.” He paused waiting for this message to sink in. “It’s now thriving and making money, thanks to me!”

Methodically he replaced his glasses and waited for our response. “Now we produce around 10% of the country’s sugar.”

His lack of modesty was almost beguiling. I was shocked to find that, despite my natural inclination to dislike him, I found I was now in danger of being captivated by his famous charm. Perhaps it’s true, I thought, what they say about money and power being a potent aphrodisiac. I was in danger of proving it so.

The two Super de Luxe Land Rovers braked outside the bright yellow refinery. Proudly Ninoy led us all inside. I was immediately struck by the smell. I supposed if you worked there you’d get used to it but to me it was sickly and overpowering, a little like stepping into a whisky distillery when you’re a teetotaller. Inside the triple-height building we saw the mountains of brown sugar rising to the ceiling like massive sand dunes. Ninoy asked one of the workers to pass around plastic spoons so we could taste the various specimens. It was quite an experience to plunge our spoons into one sugar-mountain after another, risking a possible landslide, so that we could learn to savour the different flavours.

Ninoy was beaming. He was obviously in his element. When our sweet teeth had been fully satisfied, he climbed the stairs to his office. There, with the help of close-circuit TV monitors, he showed us how he was able to view what was going on over the entire plantation. He demonstrated the intricate new alarm system he had installed recently. He wasn’t taking any chances, he said. His crop had already been sabotaged and his refinery vandalized.

“Manpowered security just doesn’t work,” he explained. “I’ve had to lay off quite a few workers now with this new system in place but it’s going to be worth it. This,” he patted the computerized machine, “is the latest thing. There’s only one other machine like it in the country. Not even Marcos has one!” He chuckled. “It cost me thousands of dollars, I can tell you, but it’s also going to save me thousands of dollars!”

I was somewhat curious why Ninoy felt the need to measure everything in dollars and not in local currency. After all, I was the only non-Filipino present and quoting in dollars would only have made more sense to me. Reading my mind, Sylvia nudged me. “Go on,” she whispered. “I dare you. Ask him!”

I couldn’t resist a challenge. So, plucking up the courage, I accepted her dare.

“Excuse me, Senator, why do you refer to everything in dollars, not in pesos?”

For a second the Boy Wonder glared at me. Then, composing himself, he smiled indulgently. “Because it’s too hard to convert. There would be too many zeros to add. I’d get confused!”

After we had been given the full Boy Wonder treatment, been inculcated by a dizzying array of facts and figures of the sugar business and been fed hundreds of his personal success stories, we felt in need of some refreshment. Ninoy packed us into the two Land Rovers and we sped back up some of the road towards the main house.

No sooner had he pulled to a stop outside the front door than the Senator looked around at us, “Anyone for a swim?” he asked.

The motion was discussed, swayed and carried. Everyone, excluding Sylvia and me, doffed their swimsuits and assembled at poolside. Naturally the ever-energetic Senator was the first to take the plunge. I noticed that he was still clutching his now, water-resistant, walkie-talkie. Surprisingly it never left his ample grip all weekend. He would use it now and again whenever he thought we were gazing at him attentively. As a matter of fact, to do the Senator justice, I believe everybody was spellbound, except me and, perhaps, Sylvia. If he had hoped to win Sylvia over to his camp this weekend so far, I felt, he had failed. There had been a fleeting moment when I was almost ready to succumb to his evident charms but that moment had long passed.

The Senator was now setting the pace. He swam two lengths of the pool. Everyone swam two lengths of the pool. He clambered out of the pool so everyone clambered out of the pool. He changed for dinner so everyone changed for dinner. He came downstairs and his guests followed him. He had a drink so everyone picked up a glass.

His wife, Cory, appeared briefly in the living room before we filed into dinner. As we sipped the last of our drinks she shook our hands and smiled graciously at us and then, just as abruptly, disappeared.

“Where’s she gone? Isn’t she going to have dinner with us?” I whispered to Sylvia.

“Oh, that’s normal here, in most Spanish mestiza households,” Sylvia replied, “when they have guests the wife will spend her time in the kitchen just to make sure everything’s OK. She’ll supervise the food, make sure it’s served properly, that kind of thing.”

Over soup, entrée and dessert “Ninoy” gave us a glimpse of his more heroic past. From the beginning to the end of the meal he didn’t stop talking. The reporters were silent as they lapped up his every word.

“When I was seventeen I was a national hero!” he proceeded. “I was the youngest newspaper reporter in Korea. None of the other Philippine journalists wanted to go to war because they had wives and families. So I volunteered. The Manila Times, agreed to send me and so I left the next day before the editor had a chance to change his mind!”

I contemplated Ninoy as the youngest war correspondent and then, for some reason, my thoughts turned to Marcos who claimed to be the youngest war hero. Again, in my mind, the similarities were striking. Although, to give Ninoy credit in this case, despite his exaggerations there were elements of truth in this particular story while every claim that Marcos made about his heroic past were later proved to be entirely bogus.

I looked at the Boy Wonder of Tarlac. He was still talking, still basking in the admiration of this handpicked group of journalists.

“Once there I became the darling of the generals. I was in on every important meeting, informed about every campaign strategy. I knew every proposed plan. All the top people confided in me. I was the baby of the press corps and they indulged me.”

He paused for audience reaction. I tried to assume an awestruck gaze such as I saw on the faces of my other dining companions. However I was unable to sustain it for long. The cynic in me refused to go away.

The Senator continued. “When I returned home after the war I was a national hero, really.”

Just in case we didn’t understand the true meaning of being a national hero, Ninoy gave us his personal definition. “I was so famous I was asked to escort Miss Philippines here, there and everywhere. Can you imagine that, at the age of seventeen?”

Now I understood perfectly what it was to be a national hero. You got to escort Miss Philippines to all the discos.

“And numerous men threatened me for driving their girlfriends to a dance. “ Ninoy continued, “One man even came into the office with a gun once and actually fired it at me!”

I’ll bet he did, I thought. T’was a pity he wasn’t a better shot.

“But, despite that, I continued escorting Miss Philippines every year.” Ninoy’s hands fidgeted with his walkie-talkie. “Even Imelda, as a matter of fact, when she was Miss Manila. But then I said to myself, why should I settle for a Miss Manila when I could have a Miss Philippines?”

Why indeed, Senator? I turned around and saw everybody, except Sylvia, nodding in awed approval. Perhaps they were simply enjoying the unlikely thought of Imelda being spurned in favour of a prettier girl with a more international title.

Enjoying the silent adulation Ninoy continued to flaunt us with his heroic exploits, naming all his newspaper chums who supported him. I realized then why the Senator never received bad press. Most of the columnists were his buddies from way back when he was a true Filipino hero. I was shocked that supposedly sane, intelligent men could be deceived by what appeared to be so monstrous an ego.

Finally, clutching his walkie-talkie, the Senator rose from the table. Pushing back their chairs everyone else rose too.

“I’m afraid to disappoint you,” he explained, “but I have to be in bed by 9.30pm because I’m in the office by 7.30am every morning.”

Don’t be afraid, Senator, I thought. You’re not disappointing me.

Aloud I said, “Excuse me, Senator, before you go!”

“Yes?”

“I just wondered if I might thank your wife for the dinner, if it’s OK?”

Ninoy paused in the doorway. He looked surprised at this request.

“Well, I suppose, yes. You’ll find her in the kitchen. It’s down the hall there!” He waved a pudgy finger in the direction of the long passageway leading off the dining room.

“Thanks, Senator. Good night!”

With Sylvia at my heels, I proceeded down the corridor towards the kitchen. As we arrived Cory was busy helping to clear away the dinner plates.

“Sorry to disturb you,” I said, unsure whether I was doing the right thing, “Sylvia and I just wanted to say thank you for the delicious meal.”

Cory smiled. “I’m glad you enjoyed it. Perhaps you’re not used to Filipino food yet?”

“I love it,” I assured her. “We’re off to bed now. I hope we’ll see you in the morning to say goodbye?”

“Perhaps,” Cory replied. “I hope you’re both comfortable in your rooms. Sleep well. If there’s anything you need, let me know.”

Sylvia and I withdrew from the kitchen with the distinct feeling we had disturbed Cory in her own personal domain.

“Don’t worry about it, Caroline. We’ll probably never see her again!” Sylvia said.

As far as political prophecies go Sylvia couldn’t have been more wrong. We certainly didn’t see Cory the next morning. She was, according to Ninoy, busy in the kitchen preparing the cooked breakfast for us all. But as Sylvia and I stood beside her in the kitchen the night before there was no way either of us could have predicted that, less than twenty years later, it would be Cory, the shy, retiring housewife from Tarlac and not her political husband who would be sitting in Malacanang Palace as President of the Philippines.

As we headed back to Manila the journalists began talking among themselves about the strange weekend. The one thing they did seem to agree on was the brilliance of our host, Ninoy Aquino. Despite his egoism, his infatuation with himself and his glaring need for adulation they had all ultimately fallen victim to his charms, whispering such obsequious remarks to one another as, “Isn’t he a marvelous man?” and “Fancy having done all that and he’s still so young!” And, scariest of all, “He’ll easily make it to the presidency. It’s in the bag. Who else is there?”

And sadly, with the amount of money the Senator was planning to spend on his presidential campaign which ran into six figures, dollars not pesos naturally, they were right. There probably was no one else.

I couldn’t wait to write the story up. And my editor, Eric Giron, couldn’t wait to print it.

“Let’s do it!” he announced beaming at me from across his desk. “It’ll be the first time anyone has dared write anything derogatory about Ninoy Aquino! Let’s see what the reaction is!” He clapped his hands as though he could already visualize the result.

The article turned out to be a devastating piece provoking endless debate in the press and over dinners in restaurants and private houses throughout the city and possibly beyond. For the first time in his political career Ninoy fell totally silent. For a full six weeks he kept his mouth shut except to consult with his advisers and to call up Eric to complain bitterly about the injustice.

“Ninoy is flabbergasted, Caroline,” Eric laughed, enjoying being at the centre of the unfolding melodrama and not untouched by the sudden leap in the popularity of his magazine. “He told me you were an uninvited house guest and how dare you accept his hospitality and then write all those atrocious things about him! I won’t even tell you the words he used about me for printing them!”

“What did you reply?” I asked.

“I just listened. He was ranting on about wanting to get his own back, write his own version of the weekend. But apparently his friends advised him against it. He said he would have started it this way,” Eric paused, “and these are his words: I just met a hippie. I thought hippies were people who were large in the hips. But this one is bigger in the head!” Eric laughed again. “So what do you make of that, Caroline?”

“Hardly the stuff great politicians are made of!” I sneered.

“Well, I think you should come down to the office and read all the letters we’ve received. You’ll be surprised how many of them support you. Listen, this will make you feel good.” I heard Eric rustling through some papers. “Here, this one…It says, writer Caroline Kennedy seems to be a brilliant British hippy sort of Mary McCarthy, or even latter-day Evelyn Waugh. She sees through the falsity of many of our values with piercing wit, discernment and, in her writing, has so little ego that she takes as many cracks at her own hippy self as she does at our Establishment.”

“Now that one I like!” I giggled. “You better frame it for me!”

Six weeks later the furore had still not died down. Eventually Ninoy’s brother, Butz, called me up to extend an olive branch.

“Can we meet?” he asked, “I’ll take you out for a meal. We do need to talk!”

I agreed. My friend, the notorious political commentator Roger “Bomba” Arienda, accompanied me to offer his support should I need it. Over lunch Butz told us, “Ninoy’s crushed, Caroline. He doesn’t know what to do. He wanted to rebut your article but we advised him against it in case it made him look like a sore loser.”

Butz lowered his eyes. I almost felt sorry for him. He seemed uncomfortable in his role as mediator. “Why I’m here, what I’ve been asked to do, Caroline, is,” Butz paused for a minute reluctant to relay the message he’d come to deliver. “Could you possibly write another one? I mean, a more favourable one?”

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing.

“But it was all true!” I protested. “Ninoy knows that. Why would I want to change it? Trouble is your brother is a show-off. He can’t help it. He asked for it, really he did.” I looked at Roger. Now was the time I needed his support.

Roger nodded. “It’s true. Caroline doesn’t tell lies!”

“I know. I know,” Butz replied, “but it’s hurt him badly. Couldn’t you just…?”

“No, I’m sorry!” I was emphatic. I had sympathy for Butz but none for the Boy Wonder. Roger, a firm believer in free speech, squeezed my hand under the table.

A few days passed and I received a message from Malacanang Palace requesting permission to reprint the article in the run-up to the 1969 presidential election. Again I refused. There was no way I would allow the Marcoses to use it as propaganda material. I had never intended it for that purpose and I could not agree to it. In the end, as it turned out, any propaganda against Marcos’s diehard opponent proved entirely unnecessary.

Six months before the election Marcos had a far bigger propaganda card up his sleeve. In July 1969, on a whistle-stop world tour, the recently elected U.S. President, Richard Nixon, stopped off in Manila and pledged his personal support of Marcos. And, lest that should not be enough to clinch the election, Marcos stole millions from the Central Bank in order to pay bribes all over the country in exchange for votes while, at the same time, barring his opponent, Sergio Osmena, Jr. access to his own funds. He also took control of all the election stations up and down the country. And in the week prior to the elections the President declared an extended national holiday and closed down the newspapers and television stations.

Now, for the second time in his political career Ninoy fell silent. Without his media friends to devote television coverage, air waves and column inches to him there was no way his voice could be heard. There was no way he could successfully challenge the incumbent President. And there was no way he could prevent Marcos from becoming the first President in Philippine history to win a second term.

This first conscious step by Marcos to remove all democratic institutions heralded the downfall of Ninoy Aquino. On the 21st September 1972 Marcos declared Proclamation 1081 instituting martial law throughout the Philippines. During the previous night many of Marcos’s political opponents including Ninoy Aquino, religious leaders, journalists, politicians, businessmen and academics were rounded up and put in prison. In the lonely confinement of his cell Ninoy, accused of murder, rape, illegal possession of firearms and subversion, wrote feverishly in his diary. Infrequently he managed to smuggle out his writings. In them he spoke of his conversion,

“It was as if I heard a voice saying: Why do you cry? I have given you…honour and glory which have been denied to millions of your countrymen. I made you the youngest war correspondent, presidential assistant, mayor, vice-governor, governor and Senator….and I recall you never thanked me for all these gifts…..Now that I visit you in your slight desolation, you cry and whimper like a spoiled brat! With this realization I went down on my knees and begged His forgiveness……In the loneliness of my solitary confinement, in the depths of my solitude and desolation….I found my inner peace. He stood me face to face with myself…..then helped me discover Him.”

Five years later, in 1978, facing the death sentence on trumped up charges of sedition, murder and gun running Ninoy Aquino, as defiant as ever, vowed to run a political campaign from the solitary confinement of his jail cell. This time he would represent his own party, People’s Power, and his target – one of the twenty-one seats in Metro Manila. His opponent would be none other than the First Lady, Imelda Marcos. If the elections, fought in April 1978, had been fair and clean, there was no doubt in anyone’s mind that Aquino and his party would have won. But, again, the Marcoses were not prepared to lose. Marcos refused to relax martial law, ballot boxes were unashamedly stuffed, bribes were paid to the teachers acting as election officials and fraud, intimidation and threats were widespread. Marcos had only called the election as a half-hearted response to U.S. President Jimmy Carter’s demand for the restoration of democracy in the Philippines. But it was a sham. Marcos’s Nacionalista Party ended up winning 98% of the vote. And, in Manila, Imelda came in first and her rival, Ninoy Aquino reportedly finished last, in 22nd place.

Soon after the election result was announced Carter reinforced his tacit support for Marcos by sending his Vice President, Walter Mondale, to Manila. During this visit Mondale signed a renewed U.S. bases agreement with Marcos, four aid programmes worth $41 million and offered $17 million worth of military hardware. He was also wined and dined regally by Imelda at Malacanang Palace.

Although Mondale agreed to meet with some of the leaders of the People’s Power Party he completely ignored its leader, Ninoy Aquino. Newspapers at the time complained bitterly about Carter’s cynicism and hypocrisy in sending Mondale to Manila so soon after such fraudulent elections. On the one hand they accused the U.S. President of deploring the lack of democracy and human rights in the Philippines while, at the same time, doing everything possible to maintain the status quo and protect U.S. national security. There was no doubt that the Marcoses benefited by the Vice President’s visit while Aquino suffered more public humiliation.

During his solitary confinement Aquino had lost a great deal of weight and had been experiencing severe chest pains. Afraid he might die in jail, Marcos gave his reluctant blessing to Aquino being moved under strict security to Imelda’s heart hospital for tests. The full complement of Manila’s press corps gathered as the ailing Senator entered the hospital. As a gesture of goodwill and forgiveness the born-again Aquino handed the gold crucifix he had been wearing around his neck in prison to his former nemesis and political rival, Imelda Marcos.

The tests revealed Ninoy required immediate surgery. This, Marcos thought, was the opportunity to rid himself of his most hated opponent for good. The President offered him safe passage to the United States hoping Ninoy would never be well enough to return to the Philippines and run for political office again.

But the politician in Ninoy hadn’t completely disappeared. He still believed he had a political destiny to fulfill in his country. Now it was just a matter of biding his time. After the successful heart operation Aquino took up a fellowship at Harvard for the next three years. Both Carter and his successor, Ronald Reagan, ignored the advice of several high-ranking members of their administrations who strongly advocated holding discussions with Aquino. The advisers instinctively knew this was the man who would be the next democratic President of the Philippines. To ignore him, they said, would be an insult to him and detrimental to the future foreign policy of the United States.

By the summer of 1983 Aquino had received word that Marcos was severely ill, perhaps dying, from lupus erythematosus, a disease of the immune system that had already seriously damaged his kidneys. Although the Palace took great pains to hide the facts about the President’s ill-health from the world, Aquino’s informer, the nephrologist Dr. Mike Baccay, told him that Marcos had undergone an unsuccessful kidney transplant at the National Kidney Center and that he was now on daily dialysis and being treated with steroid medication. Dr. Baccay was to pay dearly for his indiscretion. Two years later, on the orders of Marcos’s cousin, General Ver, he was abducted, tortured and executed in a ritualistic-style killing, receiving over one hundred stab wounds.

Aquino judged it was now time for him to return to Manila. When Imelda heard of his plans she tried her best to dissuade him with offers of money to remain in the United States. But even the new spiritual Aquino was, as always, headstrong, ambitious and willing to take the risk. He needed to be in the Philippines, he told friends, in the event of Marcos’s death so that he could run for President against Marcos’s most likely successor, Imelda.

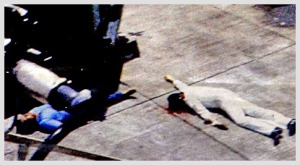

On 21st August 1983 China Airlines flight 811 circled Manila International Airport in preparation for landing. A Japanese documentary crew and several U.S. and Filipino journalists were accompanying the prodigal son, Ninoy Aquino, home. As the plane made its final approach before landing Aquino donned a bullet -proof vest. “If they hit me in the head, I’m a gonner!” he joked to the reporters.

When the plane touched down, armed officers of the Philippine Armed Forces walked up the steps to escort Aquino into the terminal. As Aquino emerged from the plane and started descending the stairs there was a momentary hail of bullets. One bullet entered Aquino’s skull from behind his left ear. In front of the world’s TV cameras the lifeless body of the Boy Wonder of Tarlac slumped to the ground below.

http://anywhereiwander.wordpress.com/2010/02/01/memoir-blog-24-ninoy-aquino-the-boy-wonder-of-tarlac/